India outlines long-term goals to scale production, reduce import dependence, boost recycling, and strengthen value chains in aluminium and copper.

In a significant move aligned with the national aspiration of becoming a developed economy by 2047, the Government of India unveiled two landmark documents: the Aluminium Vision and the Copper Vision. Released at an international mining conference in Hyderabad, these strategic blueprints outline the roadmap for transforming India into a global hub for non-ferrous metals while addressing pressing issues of resource security, sustainability, and industrial competitiveness.

These vision documents are more than sectoral policy papers. They represent the government’s broader commitment to building a self-reliant, green, and globally competitive India, while responding to the growing demand from sectors such as renewable energy, electric mobility, electronics, infrastructure, and defense. With demand for both metals expected to surge multifold by 2047, the documents provide a long-term strategy to bridge supply-demand gaps, modernize infrastructure, improve recycling, and boost value addition.

Yet, beneath this optimistic outlook lie some fundamental challenges common to both aluminium and copper sectors. These challenges have historically constrained India’s non-ferrous metal ambitions. The vision documents, however, don’t shy away from confronting these head-on. Let’s examine each challenge individually and see what the documents envision.

Watch: Top Cable Companies in India

Heavy Reliance on Imports

India’s aluminium and copper industries face an uncomfortable paradox: while the country is rich in natural reserves, it remains heavily dependent on imports, particularly for raw materials.

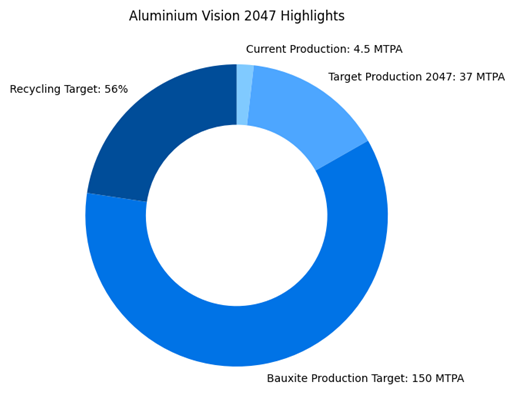

In the case of aluminium, India is the second-largest producer globally, yet it imports large quantities of bauxite, alumina, and aluminium scrap. Despite domestic reserves of around 4.95 billion tonnes of bauxite, utilization remains limited due to policy bottlenecks and lack of exploration. The Aluminium Vision document identifies this as a core vulnerability. It sets a target of achieving 100% domestic sourcing of bauxite and alumina by 2035, while scaling total aluminium production capacity from around 4.5 MTPA to 37 MTPA by 2047. Furthermore, to reduce the risk of import disruptions, the document recommends establishing dedicated mining zones, simplifying approvals, and fostering long-term linkages with end-use industries.

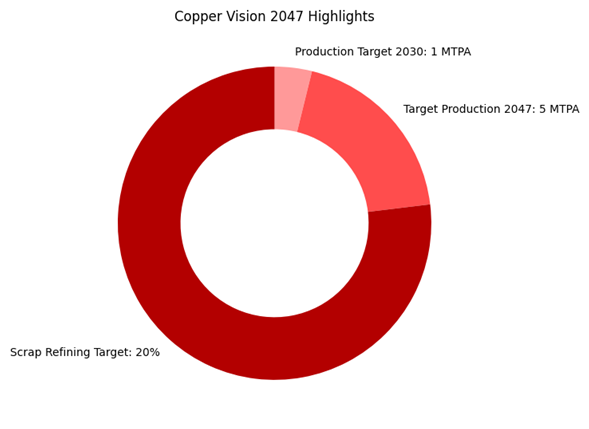

For copper, the situation is even more precarious. India imports over 90% of its copper concentrate, the essential feedstock for smelting and refining. The situation worsened after the closure of the Sterlite Copper plant in Tamil Nadu, which severely curtailed domestic refining capacity. The Copper Vision outlines the need to reverse this trajectory by adding 1 MTPA of refining capacity by 2030, and another 3.5–4 MTPA thereafter. The plan includes pursuing foreign mineral asset acquisitions, particularly in Africa and South America, while easing import duties and strengthening the resilience of supply chains.

Both vision documents thus acknowledge that true self-reliance cannot be achieved without securing upstream resources, whether through better use of domestic mines or forging overseas partnerships.

Underutilized Domestic Resources and Exploration Gaps

While India possesses significant geological potential, its conversion of inferred resources into proven reserves is suboptimal. Both aluminium and copper suffer from gaps in exploration, land access, and policy clarity.

According to the Aluminium Vision, India has identified vast bauxite deposits, but less than 5% of them are under mining lease. Delays in granting clearances and poor infrastructure in mineral-rich regions further impede development. To unlock this untapped potential, the document not only proposes targeted exploration investments and the introduction of technology-enabled mining but also lays out an ambitious production target. It aims to expand bauxite production capacity to 150 MTPA by 2047, marking a significant scale-up aligned with downstream smelting and refining goals. Streamlined environmental and forest clearances, along with rationalized royalties and levies, are recommended to improve the economic viability of these mining projects.

The Copper Vision is more candid; it states that only 18% of known geological resources have been upgraded to proven reserves. This, coupled with outdated exploration methods and low private sector participation, has left India unable to meet its domestic copper needs. The document calls for an expansion of the National Mineral Exploration Policy, competitive auctioning of exploration licenses (ELs), and enhanced coordination between state and central agencies to fast-track mineral development.

By addressing these long-standing structural gaps, both visions seek to build a stronger primary production base, reducing vulnerability to price shocks and global supply disruptions.

Low Recycling and Circular Economy Infrastructure

Despite the high recyclability of both aluminium and copper, India’s recycling infrastructure remains fragmented, informal, and underperforming.

Globally, aluminium is celebrated for its infinite recyclability and low energy footprint in secondary production. Yet, in India, only around 30–35% of aluminium comes from recycled sources. The Aluminium Vision aims to double the national aluminium recycling rate and achieve a 56% end-of-life (EoL) recycling rate by 2047, in line with global best practices. It proposes structured scrap collection systems, the formalization of informal recyclers, and investments in modern processing facilities. Tax incentives, quality standards for scrap imports, and the creation of recycling clusters are also part of the proposed framework.

In copper, India is the third-largest importer of copper scrap globally (with imports amounting to 0.310 MT in calendar year 2023), but domestic refining of scrap is minimal. With global scrap supply tightening due to export restrictions by top producers, this import-heavy model is increasingly unsustainable. The Copper Vision sets a modest but critical target: to refine 15–20% of available copper scrap by 2047. It also advocates for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks, reverse charge mechanisms (RCM), and the promotion of copper usage in easily recoverable product categories such as consumer electronics and electric vehicles.

In both sectors, building a circular economy is not only a sustainability measure, it is a strategic necessity for raw material security and cost competitiveness.

Lack of Value Addition and Processing Capacity

India’s presence in global metal trade is limited by its overreliance on primary metal exports and underdeveloped downstream processing infrastructure. This not only limits value capture but also exposes domestic industries to price volatility and quality inconsistencies.

Despite being a major aluminium producer, India contributes only 3.8% to global aluminium trade, mostly in raw or semi-processed forms. The Aluminium Vision aims to grow this share to 10% by 2047, primarily through downstream value addition. It emphasizes the establishment of Aluminium Clusters, Centers of Excellence (CoEs) for R&D, and strong linkages between primary producers and manufacturers of components, panels, and finished goods. Export competitiveness will also be bolstered by harmonizing product standards and rationalizing export-import duties.

The story is similar for copper. India’s refining and fabrication infrastructure is insufficient to meet domestic needs or compete globally. The Copper Vision proposes a shift towards making India a processing hub for copper, integrated across smelting, refining, and fabrication stages. It also suggests the creation of strategic reserves to shield downstream industries from global price volatility, alongside skill development and technological upgrades to improve efficiency.

By investing in downstream growth, both sectors seek to enhance industrial self-reliance, boost export earnings, and generate high-value employment across the supply chain.

High Cost of Production and Uncompetitive Pricing

Even as India aims to scale up its aluminium and copper capacities, a fundamental barrier to competitiveness looms large: the high cost of production. Aluminium smelters in India face some of the highest power costs globally, with electricity accounting for up to 40% of production costs. Similarly, copper smelting and refining are burdened by elevated input prices, multiple levies, and inefficient logistics.

This cost disadvantage reduces the global competitiveness of Indian producers and discourages downstream users from sourcing domestically. The Aluminium Vision identifies high energy tariffs, overlapping cesses such as DMF and NMET, and poor rail and road connectivity as major issues. It recommends rationalizing power tariffs, revisiting royalty structures, and developing dedicated logistics corridors for efficient movement of raw materials and finished products.

On the copper side, the vision document advocates for the removal of inverted duty structures, support for low-cost logistics through multimodal transport options, and export-linked benefits to incentivize scale and competitiveness.

Weak Institutional Ecosystem and Policy Fragmentation

Another deep-rooted challenge lies in the fragmented and inconsistent policy landscape that governs non-ferrous metals. Regulatory overlaps between ministries of mines, environment, commerce, and power often create confusion and delays in project approvals. The absence of integrated policy planning also hinders recycling, standardization, and innovation efforts.

Moreover, the sector suffers from weak R&D infrastructure and underinvestment in skilling and technology development. India lags in producing high-grade aluminium alloys and advanced copper conductors used in strategic sectors like EVs, defense, and renewable energy.

Both vision documents address this issue by calling for a more cohesive institutional ecosystem. The Aluminium Vision proposes the establishment of Centers of Excellence for innovation and Aluminium Clusters to foster downstream integration. It also recommends digitized single-window clearances for faster regulatory approvals.

The Copper Vision outlines the need for a national-level R&D ecosystem and coordinated scrap management systems. It also calls for inter-ministerial task forces to align quality control, incentives, and long-term planning.

Together, these measures aim to create a supportive and streamlined environment that fosters growth, innovation, and global competitiveness.

Also Read: HFCL Approves INR 125 Crore Expansion to Boost IBR Cable Capacity

A Metal-Strong Future for a Developed India

India’s aluminium and copper vision documents represent more than a policy exercise; they are a blueprint for industrial transformation and are strategic enablers of a Viksit Bharat by 2047. Both sectors are poised to play a foundational role in India’s ambitions to become a USD 30-trillion economy, achieve net-zero emissions, and establish itself as a trusted global manufacturing hub.

However, the pathway is not without hurdles. From raw material access to recycling, from refining capacity to policy clarity, the documents acknowledge that the challenges are real and pressing. Yet, they also offer a clear, actionable, and time-bound roadmap to overcome these.

What sets these visions apart is their emphasis on synergy, between mining and manufacturing, between public and private sectors, between economic growth and environmental responsibility. If implemented earnestly, these strategies could dramatically reduce India’s import dependence, boost exports, and generate robust employment in resource-rich and industrially emerging states.